First, Do No Harm: The Need for Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness

By David Treleaven, Ph.D. //

Trauma is big in the news these days. So is mindfulness. On first glance, this appears to be a good thing: But when we look deeper, things get more complicated. David Treleaven, PhD, talks about how we can implement mindfulness and meditation programs in a trauma-sensitive way.

A few months ago, I was approached with a problem by a colleague who taught meditation in a classroom setting.

Here was the issue: a student of hers had lost her father to COVID-19, and was struggling with symptoms of traumatic stress. When she’d meditate, images and sensations would flood her field of consciousness, leaving her more rattled than before.

“Should I keep meditating?” she’d asked my colleague. “I want to work with my stress, but practicing seems to be making things worse. What should I do?”

This is a conversation I’d been having for years with meditation teachers and practitioners all over the world. Given the global pandemic, this conversation has become even more frequent and intense.

What should we do when a person who is meditating is also struggling with trauma? How can we support them? And how prevalent is trauma in the first place?

Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness

Working with these questions over the past 15 years, I developed a framework of principles and modifications designed to support trauma-sensitive mindfulness meditation. A kind of “best-practices” approach to the topic, trauma-sensitive mindfulness is part of an emerging conversation about what a trauma-informed approach to mindfulness and meditation looks like.

But let’s back up for a moment.

Why would people run into trouble inside of mindfulness practice? How prevalent is trauma, anyway? And what does trauma-sensitive mindfulness actually mean?

Let’s start with the last question first.

Trauma-sensitive, or trauma-informed, practice means that we have a basic understanding of trauma in the context of our work. A trauma-informed physician can ask a patient’s permission before touching them, for example. Or a trauma-informed school counselor might ask a student whether they want the door open or closed during a session and inquire about a comfortable sitting distance. With trauma-sensitive mindfulness, we apply this concept to mindfulness instruction. As teachers, or as an organization, we commit to recognizing trauma, responding to it skillfully, and taking preemptive steps to ensure that people aren’t retraumatizing themselves under our watch.

The need for trauma-sensitive mindfulness is a reflection of both odds and statistics. Over the past decade, mindfulness has exploded in popularity. It’s now being offered in a wide range of secular environments, including elementary and high schools, corporations, and hospitals. Any number of workshops, retreats, conferences, seminars, and institutes offer mindfulness instruction. Books and articles on the subject have flooded the marketplace.

At the same time, the prevalence of trauma is extraordinarily high. The majority of us will be exposed to at least some type of traumatic event in our lifetime, and a smaller percentage of us (studies suggest 10-12%) will develop debilitating symptoms in its aftermath. What this means is that in any environment where mindfulness is being practiced, there’s a high likelihood that someone will be struggling with traumatic stress. From an employee experiencing domestic violence to a person who witnessed something horrific, trauma will often be there. And while not everyone who has experienced trauma will have an adverse response to mindfulness, we need to be prepared for this possibility.

Why do people have adverse experiences in meditation?

One important thing is that trauma often lives on inside the body – often out of view to others. Traumatic events persist in the form of petrifying sensations, emotions, and intrusive thoughts.

This is one of the most haunting, visceral costs of trauma: being forced to continually cope with gut-wrenching—often terrifying—sensations that live on inside.

Consider, then, what it means to pay mindful attention to one’s internal experience if someone is struggling with trauma. In all likelihood, this person will be brought face to face with unintegrated remnants of trauma: feelings of terror and helplessness, or disturbing memories and images.

This isn’t automatically a bad thing. Mindfulness can help us get a bit of distance from these experiences and manage them more effectively. But, when left to our own devices, we’ll tend to over-attend to stimuli that suggests we’re in danger or not okay. By paying mindful attention to what’s predominant in their field of awareness, people struggling with trauma will naturally latch on to remnants of the trauma: upsetting flashbacks, for example, or particular sensations that connect to survival-based responses like fight or flight. It’s hard to resist paying attention to these kinds of intense stimuli.

This can prove to be too much for survivors. To manage traumatic symptoms, people experiencing post-traumatic stress require more than basic mindfulness instructions to thrive. They need specific modifications to their mindfulness practice. Without this guidance, mindfulness meditation can become a setup. No matter how much sincerity they bring to their practice, they can end up being yanked into a vortex of trauma. They require tools to help them feel safe, stable, and having the ability to self-regulate.

Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness Modifications

So what can we do? Below are three tips from the 64 I write about in my book. There’s also a free list of 10 on my website, and this is a great place to start.

1. Know the Signs

Before we can respond to trauma, we first need to recognize it. As mindfulness providers, it’s up to us to notice nonverbal cues that someone is struggling with traumatic stress.

Because of the way mindfulness meditation is generally practiced, this presents a unique challenge. If you’re a meditation teacher who offers a weekly class to a group of students, how can you track people effectively? Mental-health professionals can assess trauma through direct conversation—reading facial expressions and noticing nonverbal cues—but silent meditation practice minimizes such contact.

Those of us teaching mindfulness to groups rely heavily on observation. Given that, the following are some of the basic internal and external signals that suggest someone may be outside of their window of tolerance. These are not necessarily indicators that a student or client is actively experiencing traumatic stress, but they are signals that suggest an intervention of some kind is warranted:

- Muscle tone extremely slack (collapsed, noticeably flat affect)

- Muscle tone extremely rigid

- Hyperventilation

- Exaggerated startle response

- Excessive sweating

- Noticeable dissociation (person appears highly disconnected from their body)

- Noticeably pale skin tone

- Emotional volatility (enraged, excessive crying, terror)

In conversation or interviews:

- Disorganized speech or slurring words

- Reports of blurred vision

- Inability to make eye contact during interviews/interactions

- Reports of flashbacks, nightmares, or intrusive thoughts

None of the symptoms above necessarily mean that someone is struggling with post-traumatic stress. But they can help you identify if someone needs help.

If I see someone struggling in practice, I might say something like, “I noticed during meditation that you were sweating a lot and it looked difficult for you to stand up after practice. Can we talk?” Or, “in our group interview, it appeared you were having difficulty focusing, and that you got a bit spacey. Could we sit down and talk about how practice is going for you?” All of these signs are indications someone may need more than basic meditation practice to self-regulate.

2. Offer Different Anchors

Mindfulness meditation typically involves working with something known as an object, or anchor of attention—a neutral reference point that helps support mental stability. An anchor might be the sensation of our breath coming in and out of the nostrils, or the rising and falling of our abdomen. When we become lost in thought during practice, we can return to our anchor, fixing our attention on the stimuli we’ve chosen.

But anchors can also intensify trauma. The breath, for instance, is far from neutral for many survivors. It’s an area of the body that can hold tension related to a trauma and connect to overwhelming, life-threatening events.

As a remedy, we can encourage survivors to offer people different anchors of attention. Each person’s anchor will vary: for some, it could be the sensations of their hands resting on their thighs, or their buttocks on the cushion. Other stabilizing anchors might include another sense altogether, such as hearing or sight.

Anchors of attention you can offer students and clients practicing mindfulness—besides the sensation of the breath in the abdomen or nostrils—include different physical sensations (feet, buttocks, back, hands) and other senses (seeing, smelling, hearing). One client of mine had a soft blanket that she would touch slowly as an anchor. Another used a candle. For some, walking meditation is a great way to develop more stable anchors of attention, such as the feeling of one’s feet on the ground—whatever supports self-self-regulation and stability. Experimentation is key.

3. Be an Invitation

Nobody chooses to experience trauma. Whether it’s a natural disaster, a devastating accident, or an act of interpersonal violence, trauma often leaves people feeling violated and absent a sense of control. Because of this, it’s vital that survivors feel a sense of choice and autonomy in their mindfulness practice. We want them to know that in every moment of practice, they are in control. Nothing will be forced upon them. They can move at a pace that works for them, and they can always opt out of any practice. By emphasizing self-responsiveness, we help put power back in the hands of survivors.

The body is central to this process. Trauma survivors need to know they won’t be asked to override signals from their body but listen to them.

We can accomplish this, in part, through our selection of language. Rather than give instructions as declarations, we can offer invitations that increase agency.

Here are a couple of examples:

- “In the next few breaths, whenever you’re ready, I invite you to close your eyes or have them open and downcast” (as opposed to, “close your eyes”).

- “You appeared to be hyperventilating at the end of that last meditation. Would you like to talk to me for a minute about it?” (versus, “You looked terrified. I need to talk to you”).

In all of our interactions, we can tailor our instructions to be invitations instead of commands.

Another way to emphasize choice is to provide different options in practice. We can offer students and clients the choice to have their eyes open or closed, or to adopt a posture that works best for them (e.g., standing, sitting, or lying down). Any time we are offering different ways people can practice, we can also work to normalize any choice they make—one way is not superior to the other. While we can encourage people to stay through the duration of a meditation period, we also want them to know that leaving the room—especially if they are surpassing their window of tolerance—is also an option that is always available to them.

Emphasizing choice and autonomy isn’t about coddling trauma survivors. There’s still room for structure and rigor in trauma-informed practice. But while we want to encourage people to stick with structures that will support their transformation, we never want to force structures upon them. We can extend survivors the trust that they know what is best for themselves at any given time, conveying an attitude of curiosity and respect in our instruction.

The Path Ahead

I want to be clear that I’m not saying mindfulness—or the movement in which people teach and practice it—is flawed. On the contrary, I believe it’s a profound resource for all people, and that in general, mindfulness teachers and organizations are deeply committed to the well-being of the people they work with.

At the same time, I believe we can do better. Mindfulness doesn’t need to work for everyone, but I’m convinced that certain modifications can help support survivors—at the very least ensuring that they are not re-traumatizing themselves in practice. For those of us offering mindfulness in workplaces, or other institutions, this is a competency we can develop to help make us more effective.

—

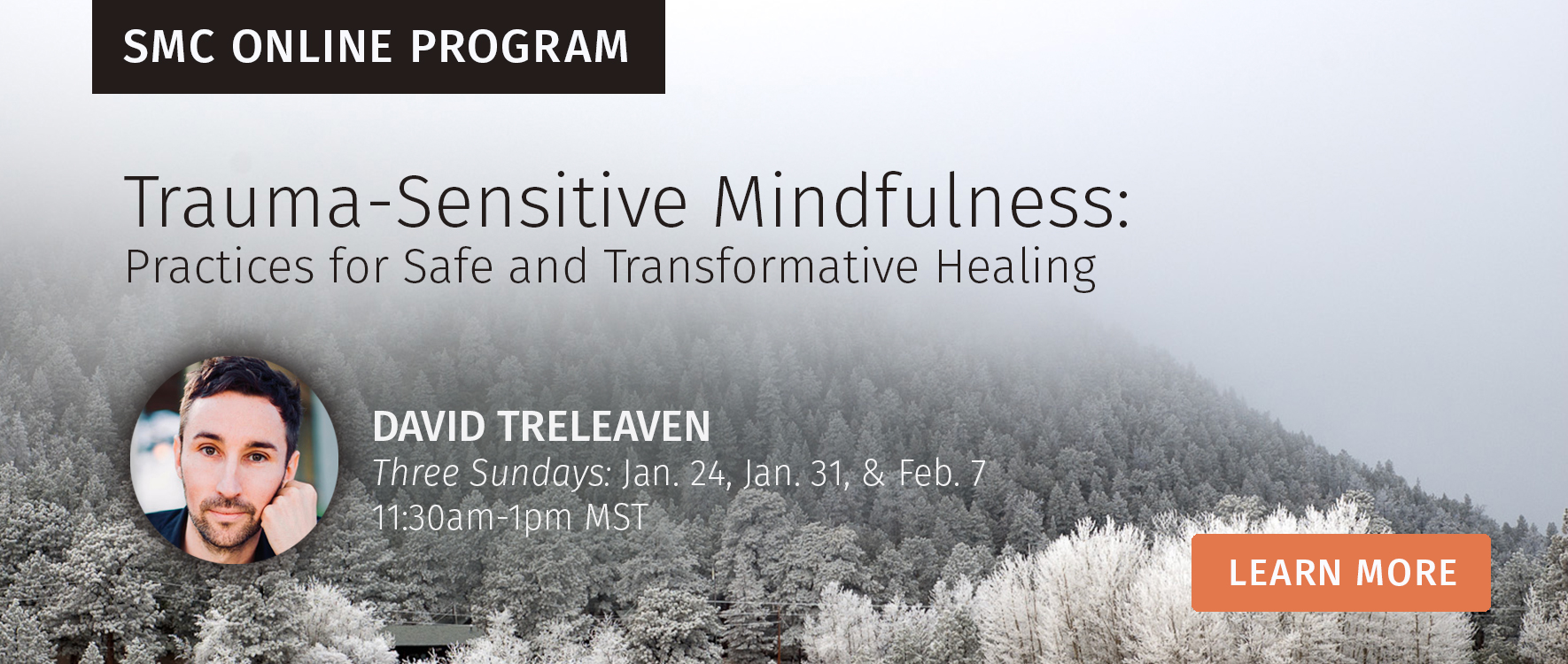

Join David Treleaven for this upcoming program:

www.davidtreleaven.com

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!